A Review with Excerpts from Magic, White & Black

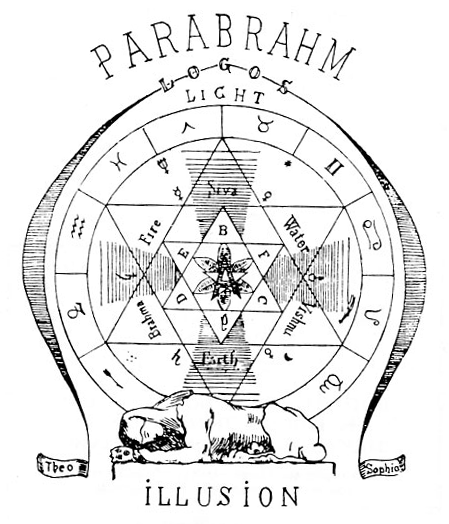

Many titles were recommended reading by Richard Rose to his students and lecture attendees, but nearest the top of the reading list, if not at the top, was Franz Hartmann’s Magic, White & Black, or The Science of Finite and Infinite Life. And there was always encouragement given by Mr. Rose to look beyond the title, which can be misleading, and crack open the book at just about any point to see that this is truly a spiritual treatise of a most profound nature. So we have chosen to print excerpts from the introduction along with chapters one, two and ten, so that those of you who have not read this book can experience firsthand a bit of the wisdom of a remarkable 19th century doctor, Franz Hartmann, M.D.

A man whose thinking parallels that of Richard Rose, “this author courageously lays down certain truths without compromise and without any appeal to the reader for the reader’s agreement. The reader soon perceives that the author possesses a great mental quantum, or else might mistakenly judge the author to be a fanatic. The reader who has previously understood the concept of an illusory life and world, will eagerly read on, waiting for the real magic of additional revelations.”

Excerpt from the Introduction

Excerpt from the Introduction

We are born into a world in which we find ourselves surrounded by physical objects. There seems to be still another—a subjective—world within us, capable of receiving and retaining impressions from the outside world. Each one is a world of its own with a relation to space different from that of the other. Each has its days of sunshine and its nights of darkness, which are not regulated by the days and nights of the other, each has its clouds and its storms, and shapes and forms of its own.

As we grow up we listen to the teachings of science to try to find out the true nature of these worlds and the laws that govern them, but physical science deals only with forms, and forms are continually changing. She gives only a partial solution of the problems of the objective world, and leaves us in regard to the subjective world almost entirely in the dark. Modern science classifies phenomena and describes events, but to describe how an event takes place is not sufficient to explain why it takes place. To discover causes, which are in themselves the effects of unknown primal causes, is only to evade one difficulty by substituting another. Science describes some of the attributes of things, but the first causes which brought these attributes into existence are unknown to her, and will remain so, until her powers of perception will penetrate into the unseen.

Besides scientific observation there seems to be still another way to obtain knowledge of the mysterious side of nature. The religious teachers of the world claim to have sounded the depths which the scientists cannot reach. Their doctrines are supposed by many to have been received through certain divine or angelic revelations, proceeding from a supreme, infinite omnipresent, and yet personal, and therefore limited external Being, the existence of which has never been proved. Although the existence of such a being is–to say the least–exceedingly doubtful, yet men in all countries have bowed down in terror before its supposed dictates; ready to tear each other’s throats at a sign of its supposed command, and willing to lay down their money, their lives, and even their honour at the feet of those who are looked upon as the confidants or deputies of a god. Men and women are willing to make themselves miserable and unhappy in life for the purpose of obtaining some reward after they live no more. Some waste their life in the anticipation of joys in a life of which they do not know whether or not it exists; some die for fear of losing that which they do not possess. Thousands are engaged in teaching others that which they themselves do not know, and in spite of a very great number of religious systems there is comparatively little religion at present upon the Earth.

The term Religion is derived from the Latin world religere, which may be properly translated “to bind back,” or to “relate.” Religion, in the true sense of the term, implies that science which examines the link which exists between man and the cause from which he originated, or in other words, which deals with the relation which exists between man and God, for the true meaning of the term “God” is Supreme First Cause, and Nature is the effect of its manifestation. True religion is therefore a science far higher than a science based upon mere sensual perception, but it cannot be in conflict with what is true in science. Only what is false in science must necessarily be in conflict with what is true in religion, and what is false in religion is in conflict with what is true in science. True religion and true science are ultimately one and the same thing, and therefore equally true; a religion that clings to illusions, and an illusory science, are equally false, and the greater the obstinacy with which they cling to their illusions the more pernicious is their effect.

A distinction should be made between “religion” and “religionism”; between “science” and “scientism”; between “mystic science” and “mysticism.”

The highest aspect of Religion is practically the union of man with the Supreme First Cause, from which his essence emanated in the beginning.

Its second aspect teaches theoretically the relations existing between that Great First Cause and Man; in other words, the relations existing between the Macrocosm and Microcosm.

In its lowest aspect religionism consists of the adulation of dead forms, of the worshipping of fetiches, of fruitless attempts to wheedle oneself into the favour of some imaginary deity, to persuade “God” to change his mind, and to try to obtain some favours which are not in accordance with justice.

Science in her highest aspect is the real knowledge of the fundamental laws of Nature, and is therefore a spiritual science, based upon the knowledge of the spirit within one’s own self.

In its lowest aspect it is a knowledge of external phenomena, and the secondary or superficial causes which produce the latter, and which our modern scientism mistakes for the final cause.

In its lowest aspect it is a knowledge of external phenomena, and the secondary or superficial causes which produce the latter, and which our modern scientism mistakes for the final cause.

In its lowest aspect scientism is a system of observation and classification of external appearances, of the causes of which we know nothing.

Religionism and Scientism are continually subject to changes. They have been created by illusions, and die when the illusions are over. True Science and true Religion are one, and if realized by Practice, they form with the truth which they contain, the three-lateral pyramid, whose foundations are upon the earth, and whose point reaches into the kingdom of heaven.

Mystic science in its true meaning is spiritual knowledge; that is to say, the soul knowledge of spiritual and “super-sensual” things, perceived by the spiritual powers of the soul. These powers are germinally contained in every human organization, but only few have developed them sufficiently to be of any practical use.

Mysticism belongs to the vapoury speculations of the brain. It is a hankering after illusions, a desire to pry into divine mysteries which the material mind cannot comprehend, a craving to satisfy curiosity in regard to what an animal ought not to know. It is the realm of fancies, of dreams, the paradise of ghost-seers, and of spiritistic tomfooleries of all kinds.

But which is the true religion and the true science? There is no doubt that a definite relationship exists between Man and the cause that called humanity into existence, and a true religion or a true science must be the one which teaches the true terms of that relation. If we take a superficial view of the various religious systems of the world, we find them all apparently contradicting each other. We find a great mass of apparent superstitions and absurdities heaped upon a grain of something that may be true. We admire the ethics and moral doctrines of our favourite religious system, and we take its theological rubbish in our bargain, forgetting that the ethics of nearly all religions are essentially the same, and that the rubbish which surrounds them is not real religion. It is evidently an absurdity to believe that any system could be true, unless it contained the truth. But it is equally evident that a thing cannot be true and false at the same time.

The truth can only be one. The truth never changes; but we ourselves change, and as we change so changes our aspect of the truth. The various religious systems of the world cannot be unnatural products. They are all the natural outgrowth of man’s spiritual evolution upon this globe, and they differ only in so far as the conditions under which they came into existence differed at the time when they began to exist; while his science has been artificially built by facts collected from external observation. Each intellectual human being, except one blinded by prejudice, recognizes the fact that each of the great religious systems of the world contains certain truths, which we intuitively know to be true; and as there can be only one fundamental truth, so all these religions are branches of the same tree, even if the forms in which the truth manifests itself are not alike. The sunshine is everywhere the same, only its intensity differs in different localities. In one place it induces the growth of palms, in another of mushrooms; but there is only one Sun in our system. The processes going on on the physical plane have their analogies in the spiritual realm, for there is only one Nature, one Law.

If one person quarrels with another about religious opinions, he cannot have the true religion, nor can he have any true knowledge; because true religion is the realization of truth. The only true religion is the religion of universal Love; this love is the recognition of one’s own divine universal self. Love is an element of divine Wisdom, and there can be no wisdom without love. Each species of birds in the woods sings a different tune; but the principle which causes them to sing is the same in each. They do not quarrel with each other, because one can sing better than the rest. Moreover, religious disputation, with their resulting animosities, are the most useless things in the world; for no one can combat the darkness by fighting it with a stick; the only way to remove darkness is to kindle a light, the only way to dispel spiritual ignorance is to let the light of knowledge that comes from the center of love shine into every heart.

All religions are based upon internal truth, all have an outside ornamentation which varies in character in the different systems, but all have the same foundation of truth, and if we compare the various systems with one another, looking below the surface of exterior forms, we find that this truth is in all religious systems one and the same. In all this, truth has been hidden beneath a more or less allegorical language, impersonal and invisible powers have been personified and represented in images carved in stones or wood, and the formless and real has been pictured in illusive forms. These forms in letters, and pictures, and images are the means by which truths may be brought to the attention of the unripe Mind. They are to the grown-up children of all nations what picture-books are to small children who are not yet able to read, and it would be as unreasonable to deprive grown-up children of their images before they are able to read in their own hearts, as it would be to take away the picture-books from little children and to ask them to read printed books, which they cannot yet understand.

Excerpt from Chapter 1, “The Ideal”

“God is a Spirit, and they that worship him must worship him in spirit and in truth.” –John iv. 24.

The highest desire any reasonable man can cherish and the highest right he may possibly claim, is to become perfect. To know everything, to love all and be known and beloved by all, to possess and command everything that exists, such is a condition of being that, to a certain extent, may be felt intuitively, but whose possibility cannot be grasped by the intellect of mortal man. A foretaste of such a blissful condition may be experienced by a person who—even for a short period of time—is perfectly happy. He who is not oppressed by sorrow, not excited by selfish desires, and who is conscious of his own strength and liberty, may feel as if he were the master of worlds and the king of creation; and, in fact, during such moments he is their ruler, as far as he himself is concerned, although his subjects may not seem to be aware of his existence.

But when he awakes from his dream and looks through the windows of his senses into the exterior world, and begins to reason about his surroundings, his vision fades away; he beholds himself a child of the Earth, a mortal form, bound with many chains to a speck of dust in the Universe, on a ball of matter called a planet that floats in the infinity of space. The ideal world, that perhaps a moment before appeared to him as a glorious reality, may now seem to him the baseless fabric of a dream, in which there is nothing real, and physical existence, with all its imperfections, is now to him the only unquestionable reality, and its most dear illusions the only things worthy of his attention. He sees himself surrounded by material forms, and he seeks to discover among these forms that which corresponds to his highest ideal.

The highest desire of mortal is to attain fully that which exists in himself as his highest ideal. A person without an ideal is unthinkable. To be conscious is to realize the existence of some ideal, to relinquish the ideal world would be death. A person without any desire for some ideal would be useless in the economy of nature, a person having all his desires satisfied needs to live no longer, for life can be of no further use to him. Each one is bound to his own ideal; he whose ideal is mortal must die when his ideal dies, he whose ideal is immortal must become immortal himself to attain it.

Each man’s highest ideal should be his own higher spiritual self. Man’s semi-animal self, which we see expressed in his physical form, is not the whole of man. Man may be regarded as an invisible power or ray extending from the (spiritual) Sun to the Earth. Only the lower end of that ray is visible, where it has evolved an organized material body; by means of which the invisible ray draws strength from the earth below. If all the life and thought-force evolved by the contact with matter are spent within the material plane, the higher spiritual self will gain nothing by it. Such a person resembles a plant developing nothing but its root. When death breaks the communication between the higher and lower, the lower self will perish, and the ray will remain what it was, before it evolved a mortal inhabitant of the material world.

Man lives in two worlds, in his interior and in the exterior world. Each of these worlds exists under conditions peculiar to itself, and that world in which he lives is for the time being the most real to him. When he enters into his interior world during deep sleep or in moments of perfect abstraction, the forms perceived in the exterior world fade away; but when he awakes in the exterior world the impressions received in his interior state are forgotten, or leave only their uncertain shadows on the sky. To live simultaneously in both worlds is only possible to him who succeeds in harmoniously blending his internal and external worlds into one.

The so-called Real seldom corresponds with the Ideal, and often it happens that man, after many unsuccessful attempts to realize his ideals in the exterior world, returns to his interior world with disappointment, and resolves to give up his search; but if he succeeds in the realization of his ideal, then arises for him a moment of happiness, during which time, as we know it, exists for him no more, the exterior world is then blended with his interior world, his consciousness is absorbed in the enjoyment of both, and yet he remains a man.

Artists and poets may be familiar with such states. An inventor who sees his invention accepted, a soldier coming victorious out of the struggle for victory, a lover united with the object of his desire, forgets his own personality and is lost in the contemplation of his ideal. The extatic saint, seeing the Redeemer before him, floats in an ocean of rapture, and his consciousness is centred in the ideal that he himself has created out of his own mind, but which is as real to him as if it were a living form of flesh. Shakespeare’s Juliet finds her mortal ideal realized in Romeo’s youthful form. United with him, she forgets the rush of time, night disappears, and she is not conscious of it; the lark heralds the dawn and she mistakes its song for the singing of the nightingale. Happiness measures no time and knows no danger. But Juliet’s ideal is mortal and dies; having lost her ideal Juliet must die; but the immortal ideals of both become again one as they enter the immortal realm through the door of physical death.

But as the sun rose too early for Juliet, so all evanescent ideals that have been realized in the external world vanish soon. An ideal that has been realized ceases to be an ideal; the ethereal forms of the interior world, if grasped by the rude hand of mortals and embodied in matter, must die. To grasp an immortal ideal, man’s mortal nature must die before he can grasp it.

Low ideals may be killed, but their death calls similar ones into existence. From the blood of a vampire that has been slain a swarm of vampires arises. A selfish desire fulfilled makes room for similar desires, a gratified passion is chased away by other similar passions, a sensual craving that has been stilled gives rise to new cravings. Earthly happiness is short-lived and often dies in disgust; the love of the immortal alone is immortal. Material acquisitions perish, because forms are evanescent and die. Intellectual accomplishments vanish, for the products of the imagination, opinions, and theories, are subject to change. Desires and passions change and memories fade away. He who clings to old memories, clings to that which is dead. A child becomes a man, a man an old man, an old man a child; the playthings of childhood give way to intellectual playthings, but when the latter have served their purpose, they appear as useless as did the former, only spiritual realities are everlasting and true. In the ever-revolving kaleidoscope of nature the aspect of illusions continually changes its form. What is laughed at as a superstition by one century is often accepted as the basis of science for the next, and what appears as wisdom to-day may be looked upon as an absurdity in the great to-morrow. Nothing is permanent but the truth.

But where can man find the truth? If he seeks deep enough in himself he will find it revealed, each man may know his own heart. He may let a ray of the light of intelligence into the depths of his soul and search its bottom, he will find it to be as infinitely deep as the sky above his head. He may find corals and pearls, or watch the monsters of the deep. If his thought is steady and unwavering, he may enter the innermost sanctuary of his own temple and see the goddess unveiled. Not everyone can penetrate into such depths, because the thought is easily led astray; but the strong and persisting searcher will penetrate veil after veil, until at the innermost center he discovers the germ of truth, which, awakened to self-consciousness, will grow in him into a sun that illuminates the whole of his interior world.

Such an interior meditation and elevation of thought in the innermost center of the soul, is the only true prayer. The adulation of an external form, whether living or dead, whether existing objectively or merely subjectively in the imagination, is useless, and serves only to deceive. It is very easy to attend to forms of external worship, but the true worship of the living God within requires a great effort of will and a power of thought, and is in fact the exercise of a spiritual power received from God. God in us prays to himself. Our business consists in continual guarding of the door of the sacred lodge, so that no illegitimate thoughts may enter the mind to disturb the holy assembly whose deliberations are presided over by the spirit of wisdom.

How shall we know the truth? It can be known only if it becomes revealed within the soul. Truth, having awakened to consciousness, knows that it is; it is the god-principle in man, which is infallible and cannot be misled by illusions. If the surface of the soul is not lashed by the storms of passion, if no selfish desires exist to disturb its tranquility, if its waters are not darkened by reflections of the past, we will see the image of eternal truth mirrored in the deep. To know the truth in its fullness is to become alive and immortal, to lose the power of recognizing the truth is to perish in death. The voice of truth in a person that has not yet awakened to spiritual life, is the “still small voice” that may be heard in the heart, listened to by the soul, as a half-conscious dreamer listens to the ringing of bells in the distance,* but in those that have become conscious of life, having received the baptism of the first initiation administered by the spirit of God, the voice heard by the new-born ego has no uncertain sound, but becomes the powerful Word of the Master. The awakened truth is self-conscious and self-sufficient, it knows that it exists. It stands higher than all theories and creeds and higher than science, it does not need to be corroborated by “recognized authorities,” it cares not for the opinion of others, and its decisions suffer no appeal. It knows neither doubt nor fear, but reposes in the tranquility of its own supreme majesty. It can neither be altered nor changed, it always was and ever remains the same, whether mortal man perceives it or not. It may be compared to the light of the earthly sun, that cannot be excluded from the world, but from which man may exclude himself. We may blind ourselves to the perception of the truth, but the truth itself is not thereby changed. It illuminates the minds of those who have awakened to immortal life. A small room requires a little flame, a large room a great light for its illumination, but in either room the light shines equally clear in each; in the same manner the light of truth shines into the hearts of the illumined with equal clearness, but with a power differing according to their individual capacity.

It would be perfectly useless to attempt to describe this interior illumination. Only that which exists relatively to ourselves has a real existence for us, that of which we know nothing does not exist for us. No real knowledge of the existence of light can be furnished to the blind, no experience of transcendental knowledge can be given to those whose capacity to know does not transcend the realm of external appearances.

*See H.P. Blavatsky: “The voice of the silence.”

Excerpts from Chapter 10, “Creation”

Man in his youth longs for the material pleasures of earth, for the gratification of his physical body. As he advances, he throws away the playthings of his childhood and reaches out for something higher. He enters into intellectual pursuits, and after years of labour he may find that he has been wasting his time by running after a shadow. Perhaps love steps in and he thinks himself the most fortunate of mortals, only to find out, sooner or later, that ideals can only be found in the ideal world. He becomes convinced of the emptiness of the shadows he has been pursuing, and, like the winged butterfly emerging from the chrysalis, he stretches out his feelers into the realm of infinite spirit, and is astonished to find a radiant sun where he only expected to find darkness and death. Some arrive at this light sooner; others arrive later, and many are lured away by some illusive light and perish, and like insects that mistake the flame of a candle for the light of the sun, scorch their wings in its fire.

Life is a continual battle between error and truth; between man’s spiritual aspirations and the demands of his animal instincts. There are two gigantic obstacles in the way of progress: his misconception of the nature of God and of Man. As long as man believes in an extracosmic personal God distributing favours to some and punishing others at pleasure, a God that can be reasoned with, persuaded, and pacified by ignorant man, he will keep himself within the narrow confines of his ignorance, and his mind cannot expand. To think of some place of personal enjoyment or heaven, does not assist man’s progression. If such a person desists from doing a wicked act, or denies himself a material pleasure, he does not do so from any innate love of good; but either because he expects a reward from God for his “sacrifice,” or because his fear of God makes him a coward. We must do good, not on account of any personal consideration, but because to do good is our duty. To be good is to be wise, the fool expects rewards; the wise expects nothing. The wise knows that by benefiting the world he benefits himself, and that by injuring others he becomes his own executioner.

What are the powers of Man, by which he may benefit the world? Man has no powers belonging to himself. Even the substance of which his organization is made up, does not belong but is only lent to him by Nature, and he must return it. He cannot make any use of it, except through that universal power, which is active within his organization, which is called the Will, and which itself is a function of an universal principle, the Spirit.

Man as a personal and limited being is merely a manifestation of this universal principle in an individual form, and all the spiritual powers he seems to possess belong to the Spirit. Like all other forms in nature he receives life, light, and energy from the universal fountain of Life, and enjoys their possession for a short span of time; he has no powers whatever which he may properly call his own.

Thus the sunshine and rain, the air and earth, does not belong to a plant. They are universal elements belonging to nature. They come and help to build up the plant, they assist in the growth of the rosebush as well as the thistle; their business is to develop the seed, and when their work is done, the organism in which they were active returns again to its mother, the Earth. There is then nothing which properly belongs to the plant; but the seed continues to exist without the parental organism after having attained maturity, and in it is contained the character of the species to which it belongs.

Life, sensation, and consciousness are not the property of personal man; neither does he produce them. They are functions of the Spirit and belong originally to God. The One Life furnishes the principles which go to build up the organism called Man, the forms of the good as well as those of the wicked. They help to develop the germ of Intelligence in man, and when their work is done they return again to the universal fountain. The germ of Divinity is all there is of the real man, and all that is able to continue to exist as an individual, and it is not a man, but a Spirit, one and identical in its essence with the Universal God, and one of his children. How many persons exist in whom this divine germ reaches maturity during their earthly life? How many die before it begins to sprout? How many do not even know that such a germ exists?

To this Universal Principle belong the functions which we call Will and Life and Light; its foundation is Love. To it belong all the fundamental powers which produced the universe and man, and only when man has become one and identical with God or to speak more correctly, when he has come to realize his oneness with God, can he claim to have powers of his own.

But the Will of this Universal Power is identical with universal Law, and man who acts against the Law acts against the Will of God, and as God is man’s only real eternal Self, he who acts against that Law destroys himself.

The first and most important object of man’s existence is, therefore, that he should learn the law of God and of Nature, so that he may obey it and thereby become one with the law and live in God. A man who knows the Law knows himself, and a man who knows his divine Self knows God.

The only power which man may rightfully claim his own is his Self-knowledge; it belongs to him because he has required it by the employment of the powers lent to him by God. Not the “knowledge” of the illusions of life, for such knowledge is illusive, and will end with those illusions, not mere intellectual learning, for that treasure will be exhausted in time; but the spiritual self-knowledge of the heart, which means the power to grasp the truth which exists in ourselves.

What has been said about the Will is equally applicable to the Imagination. If man lets his own thoughts rest, and rises up to the sphere of the highest ideal, his mind becomes a mirror wherein the thoughts of God will be reflected, and in which he may see the past, the present, and future; but if he begins to speculate within the realm of illusions, he will see the truth distorted and behold his own hallucinations.

The knowledge of God and the knowledge of man are ultimately identical, and he who knows himself knows God. If we understand the nature of the divine attributes within us, we will know the Law. It will then not be difficult to unite our Will with the supreme Will or the cosmos; and we shall be no longer subject to the influences of the astral plane, but be their masters. Then will the Titans be conquered by the gods; the serpent in us will have its head crushed by Divine Wisdom; the devils within our own hells will be conquered, and instead of being ruled by illusions, we shall be ruled by Wisdom.

It is sometimes said that it does not make any difference what a man believes so long as he acts rightly; but a person cannot be certain to act rightly, unless he knows what is right. The belief of the majority is not always the correct belief, and the voice of reason is often drowned in the clamour of a superstition based upon erroneous theological doctrine. An erroneous belief is detrimental to progress in proportion as it is universal; such belief rests on illusion, knowledge is based on truth. The greatest of all religious teachers therefore recommended Right Belief as being the first step on the Noble Eightfold Path.*

Perhaps it will be useful to keep in mind the following rules—

1. Do not believe that there is anything higher in the universe than your own divine self, and know that you are exactly what you permit yourself to become. The true religion is the recognition of divine truth; idols are playthings for children.

2. Learn that man is essentially a component and integral part of universal humanity, and that what is done by one individual acts and reacts on all.

3. Realise that man’s nature is an embodiment of ideas, and his physical body an instrument which enables him to come into contact with matter; and that this instrument should not be used for unworthy purposes. It should neither be worshipped nor neglected.

4. Let nothing that affects your physical body, its comfort, or the circumstances in which you are placed, disturb the equilibrium of your mind. Crave for nothing on the material plane, live about it without losing control over it. Matter forms the steps upon which we may ascend to the kingdom of heaven.

5. Never expect anything from anybody, but be always ready to assist others to the extent of your ability, and according to the requirements of justice. Never fear anything but to offend the moral law and you will not suffer. Never hope for any reward and you will not be disappointed. Never ask for love, sympathy, or gratitude from anybody, but be always ready to bestow them on others. Such things come only when they are not desired.

6. Learn to distinguish and to discriminate between the true and the false, and act up to your highest ideal. Grieve not if you fall, but rise and proceed on your way.

7. Learn to appreciate everything (yourself included) at its true value in all the various planes. A person who attempts to look down upon one who is his superior is a fool, and a person who looks up to one who is inferior is mentally blind. It is not sufficient to believe in the value of a thing, its value must be realistd, otherwise it resembles a treasure hidden in the vaults of a miser.

*The eight stages on the Noble Eightfold Path to find the truth are, according to the doctrine of Gautama Buddha, the following—

- Right Belief.

- Right Thought.

- Right Speech.

- Right Doctrine.

- Right Means of Livelihood.

- Right Endeavour.

- Right Memory.

- Right Meditation.

The man who keeps these augas in mind and follows them will be free from sorrow, and may become safe from future rebirths with their consequent miseries.

To order a copy of Hartmann’s book, please visit our book section.